HEARING CONCERNS AND STARTING A DIALOGUE

The first step in finding opportunities to engage with a network is to track and understand the challenges in the system you are hoping to improve. Grantmakers at The Rockefeller Foundation recognized a potential to act when health officials in a number of Southeast Asian nations separately shared their deep concern about the risk of a pandemic emerging in a neighboring country that wouldn’t be visible until it had already spread across the border. Early detection is crucial to meeting the threat of a new disease while it remains in an area that is small enough that it can still be contained. Representatives from the health ministries from these nations saw the need to build not only national capacity for disease detection, but also a means for lateral information-sharing across countries, yet there was little support in place for either one.

This idea took form in February of 1999 when the Foundation invited representatives from the ministries of health of the six Mekong Basin countries to a consultative meeting with the World Health Organization: Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, and the southern province of China. The topic: what mechanisms could strengthen disease surveillance across the sub-region? The group decided to take action in three areas: improving disease outbreak investigation and response, developing human capacity in field epidemiology, and establishing the Mekong Basin Disease Surveillance Network.

BUILDING TRUST AND SPARKING COLLABORATION

The key question for the grantmakers at this early stage of the network was what type of relationships and activities within the group would best accomplish its goal. They realized that the most important missing piece was trust, and that while trust can’t be created, it can be given a chance to grow. Charlanne Burke, now a Senior Program Associate at The Rockefeller Foundation, was part of the team involved in the formation of the network and remembers how important it was that this trust was formed through personal ties at the staff level rather than by working through formal Ministerial channels. “They certainly weren’t working in secret, but it was not a formal government network,” she recalls. “That gave them the latitude to work in the cracks and share information without going through formal protocols. The result was to add a new flexibility and informality into the system.”

Between helping build each nation’s disease surveillance capacity and fostering the formation of the new network, the Foundation’s program officers played a fairly hands-on role in the beginning. “There was a lot of one-on-one with the principle investigators, lots of advising, and lots of troubleshooting,” Burke reflects.

A principal goal of this hands-on approach was to make use of the non-governmental nature of the network to forge enough personal trust among the participants that they felt comfortable sharing important information. That trust was forged through face-to-face activities, such as tabletop simulation exercises and joint investigations undertaken together by network members. This combination of network-weaving and capacity-building produced a collaboration strong enough that the six countries were able to agree on common reporting standards and integrate the disease-related work of many of their local, regional, and national health officials. This smarter coordination and deeper connection enabled joint investigation and response to a dengue fever outbreak between Laos and Thailand in 2005, a typhoid and malaria outbreak between Laos and Vietnam in 2006, and an avian flu outbreak between Laos and Thailand in 2007.

SPREADING THE MODEL AND STEPPING BACK

When a network is successful, it can inspire other groups to want to collaborate in similar ways, giving grantmakers an opportunity to support the replication of an emerging new model. As the Mekong Basin network began to show promise, it spurred both The Rockefeller Foundation and others to build similarly-structured networks in other regions that had a high risk of producing new pandemics. In the early 2000s the Foundation’s grantmakers began collaborating with the World Health Organization and East African health officials to support the creation of the East African Integrated Disease Surveillance Network. In 2008, the UK government, the Wellcome Trust, and African human and animal health experts established a similar model in southern Africa which became the Southern African Centre for Infectious Disease Surveillance. Similar networks emerged in Southeastern Europe and the Middle East.

When many networks emerge around the same issue, a funder’s field-level view can be useful in exploring whether a network of networks would be valuable. As officers at the Nuclear Threat Initiative saw the spread of these regional networks, they began to wonder if a network of networks could allow even greater information exchange and peer learning between regions. The Foundation organized a convening at its Bellagio center to pose the question of whether that level of connectivity would be valuable. As a result of that dialogue four funders came together – The Peter G. Peterson Foundation, The Rockefeller Foundation, The Skoll Global Threats Fund and the Nuclear Threat Initiative – to form a new peer learning network in 2009. That network, Connecting Organizations for Regional Disease Surveillance (CORDS), now uses just two permanent staff and three consultants to facilitate communication and information exchange among six regional networks.

Exiting network funding is rarely easy, but after making over $20 million of philanthropic investments in disease surveillance over 14 years, the Foundation concluded its Disease Surveillance Networks initiative in 2012. To ease the transition, its grantmakers gave the Mekong Basin Disease Surveillance Network guidance on fundraising and a final grant to re-form the informal network into a formal entity that could seek its own funding, the MBDS Foundation. But its ties to the work are far from cut. Grantmakers, including Burke and her colleagues in Bangkok and Nairobi, continue to serve on regional networks’ boards and provide advice. And as of the time of this writing, the Foundation continues to support CORDS, such as through its recent funding to support CORDS members in sharing expertise with their West African counterparts in responding to the recent devastation caused by Ebola and developing a West African Disease Surveillance Network. In this way, the Foundation is continuing to build connectivity within the new infrastructure of regional disease surveillance that it seeded over the past two decades.

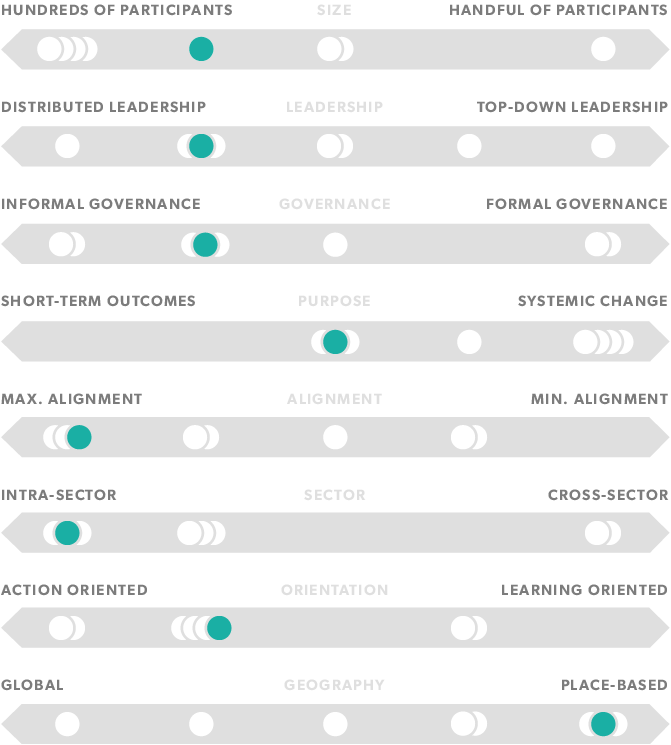

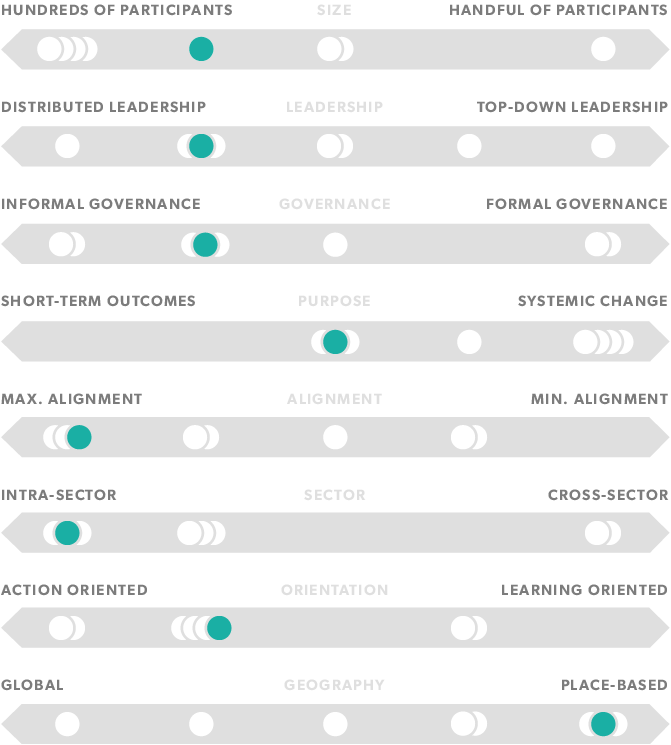

BY COMPARISON: THE NETWORK’S DESIGN

In the section What network design would be most useful? we introduce a simple framework for comparing the ‘design’ of a network — eight basic variables that define its shape and size. See below for our estimation of the Mekong Basin Disease Surveillance Network’s design (in teal) versus that of the other networks we profile (in white):

Sources: The Rockefeller Foundation Initiative: Disease Surveillance Networks (2013); an interview with Charlanne Burke, Senior Program Associate at The Rockefeller Foundation (fall 2014); and, the websites of the MBDS Foundation, CORDS, and the Nuclear Threat Initiative.