THE POWER OF A COLLECTIVE REFRAME

Like most efforts, Reimagine Learning started with a conversation. In 2012, Vanessa Kirsch, head of New Profit, a Boston-based venture philanthropy fund, and some of the trustees of The Peter and Elizabeth C. Tower Foundation, discussed their views on how students with learning and attention issues remain at the margins of the mainstream education reform movement, even as schools make big improvements in other ways. They were talking about students with dyslexia, ADHD, dyscalculia and other brain-based difficulties that make learning challenging and that can also lead to social and emotional challenges—students who are very unlikely to get the support they need in an “average” classroom environment.

Meanwhile, another reality perplexing New Profit was their observation that many social entrepreneurs in the field of learning differences and in the field of social and emotional learning had been ambitiously broadening the scope of their program models, working up and down the value chain to take on more of their chosen issue. They were doing good work individually, but many of these social change leaders were looking for ways to broaden their impact even further through partnership. There was a growing hunch that helping bridge these fields, both with important innovations and perspectives on how kids learn, would be critical.

Supporting partnerships between like-minded organizations is one thing. Building bridges between separate fields is another. And to support this effort through a funder collaborative, requiring another level of collaboration, posed yet another set of challenges. As Shruti Sehra, partner at New Profit and lead of the Reimagine Learning network, put it: “We saw all kinds of programs expanding their models because they realized they were just one piece of the puzzle. And leaders would wonder, ‘How much do we keep expanding?’ But yet, when we would get them in the same room together, inevitably they would talk about how they could do more together than they could on their own. So we started to ask ourselves, ‘What would it look like if we approached social change from a network perspective?’ What would it take for social entrepreneurs? What would it take for funders?”

The importance of this intuition in bridging siloed fields was shared by other funders who were starting to engage with New Profit around this idea. Stacy Parker-Fisher, Director of the Learning Differences Program at Oak Foundation, recalled: “We wanted to reframe the problem, to change the conversation from one about special education and learning disabilities to a conversation about how many kids are not being successful in school simply because of how they learn. If we had only focused on kids with learning disabilities, we would have been missing so many students.” Tracy Sawicki, executive director of The Peter and Elizabeth C. Tower Foundation, remembers thinking along similar lines. “There weren’t a lot of people working together in these two fields. There was a spirit among the funders that we might be able to figure this out on a larger scale if we came together.”

THE HARD WORK OF AGREEING TO WORK TOGETHER

As the idea of a new network took form, the four co-funders worked to find productive ways of working together themselves. While funders at Oak, Poses and Tower had already been working together to arrive at a shared vision around the biggest needs and opportunities in the field, as Parker-Fisher from Oak Foundation remembers: “It took quite a while for the funders to realize that we didn’t all need to do everything the same. After all, we represent different families. Then we started thinking of it as a Venn diagram, and looked for that space of crossover where we can support the field by leveraging what’s unique to each funder’s capabilities or vision.”

The group agreed that establishing a collaboration built on co-creation was the goal. They also realized that this would be quite different from typical co-funding relationships. Shelly London, President of the Poses Family Foundation, was one of several voices who pushed for a set of formal agreements that would spell out exactly what co-creation would require, ensuring that the group was strategically aligned on how they were going to drive impact. “It was vital for us to have the difficult conversations up front. You have to talk about what it means to co-create, how you’re going to work together, and how you’re going to achieve the best results. Investing this time early on made things go more smoothly when the real work began.”

Forging those agreements was difficult. The collaborative work hadn’t yet begun; while each participant believed they understood how they could contribute to the collective effort, they hadn’t yet articulated their views in detail, so it wasn’t yet possible to know precisely where their visions differed. While it took substantial conversation, the agreements came out as London had hoped, giving the funders clear voting rights and laying out the principles that would guide their co-creative work. With the agreements signed, the funders collectively agreed to spend $30 million together over the coming five years in support of the network, including funds to support the social entrepreneurs, network facilitation and policy experts.

Not all networks involve such a detailed up-front negotiation, but this would represent a very significant investment for some of the funders involved. One particularly striking example: The Peter and Elizabeth C. Tower Foundation switched from giving many smaller grants, in the range of $125,000 each, to making a single multi-year investment of $10 million to help launch the Reimagine Learning network.

SEEING THE ROI ON TIME INVESTED

As is often the case with the founding participants of a network, the funders found this collaborative effort somewhat more time-consuming than they had expected, but also saw it to have undeniable power. Ashley Sandvi, Vice President of Strategy and Operations at The Poses Family Foundation, was one participant who found the time commitment to be even higher than she’d expected. “What might not be self-evident to many funders is how much time it really takes to incubate complex collaborations. Quite frankly, I knew it was going to be a big key for organizations to work together, but I didn’t know it would take all of the partners rolling up their sleeves at every step of the way,” she shares.

Oak Foundation also had to adjust its expectations. Oak initially saw the network as a well-staffed group that it could trust to re-invest its funds in a way that would move the field forward while allowing its staff to turn its attention to other initiatives, but the actual time investment required turned out to be an average of one full day a week of Parker-Fisher’s time. She recalls having to assess the value of this investment with her team: “When we moved into this collaborative role, I didn’t expect it to be a significant part of my work. As it emerged to become a significant time commitment, we did a step-back to ask what part of this work was critical. But participation has been a huge accelerant for our ability to form important connections and make good grants.”

This investment of time also allowed the group to address its disagreements primarily through consensus-building rather than the formal voting process. Sehra, whose time investment has been close to three-quarters of her own time with the support of a partner, a half-time manager and a full-time analyst, concurs that the output was greatly improved as a result. “There’s no question that it is incredibly time-consuming to have co-creators at the table, not to mention co-voters. But when we engage them, we engage them authentically. And I know the content we’ve landed on is far, far better than if we had done this alone.”

WHAT THE COLLABORATIVE WORK HAS ACHIEVED

With the ground rules in place, the funders were ready to engage and the new network’s collaborative work could begin. To help facilitate the process and craft the network’s strategy, Monitor Institute joined to help the participants understand where they agreed and where they did not, allowing New Profit to step into more of a participant role. Through meetings, research, interviews, and a lot of deep listening to one another, the group gained a broader sense of the context in which the network operated and the future the network could collectively influence. This dialogue built mutual understanding of what the participants believed, whom they served, what problem they solved, and how they had made a difference, all of which enabled them to draft a shared vision for how to change the education system in ways that would produce far stronger results than continuing to work alone.

Fast-forward to today, and those who participate in Reimagine Learning are now united by three core beliefs:

- There is no such thing as an average learner. Sharing the same classroom does not mean sharing the same mind.

- The best learning environments equally value and cultivate cognitive, social, and emotional skills and understand that together they drive academic performance, well-being, and life success.

- It is critical that students have a say in their own learning journey: what they learn, how and where they learn it.

The network’s participants include innovative entrepreneurial organizations like ANet, Eye to Eye, New Classrooms Innovation Partners, New Teacher Center, Peace First, and Turnaround for Children, and they are now starting to collaborate on projects that put their ideas into action:

- New Teacher Center and the University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning are distilling research findings to equip teachers with instructional resources.

- Together, 15 non-profit organizations that care deeply about helping kids with learning and attention issues (many of which are members of Reimagine Learning) came together to launch Understood.org, a free and comprehensive resource for parents.

- City Year will open a new school, Compass Academy, which will build on its insights from working with at-risk students for over two decades.

- MIT Media Lab will expand its work to create technologies that support students who learn in different ways and help them take charge of their own education.

- With New Profit’s policy arm, America Forward, the network is also focused on pushing for policy changes to remove barriers and create incentives that support new types of teaching and learning environments.

The network is now in a strong position to continue building its influence over the coming three years. The funders’ co-creative partnership has stayed resilient to date, and when the five-year mark arrives in 2017 they will formally re-evaluate their roles.

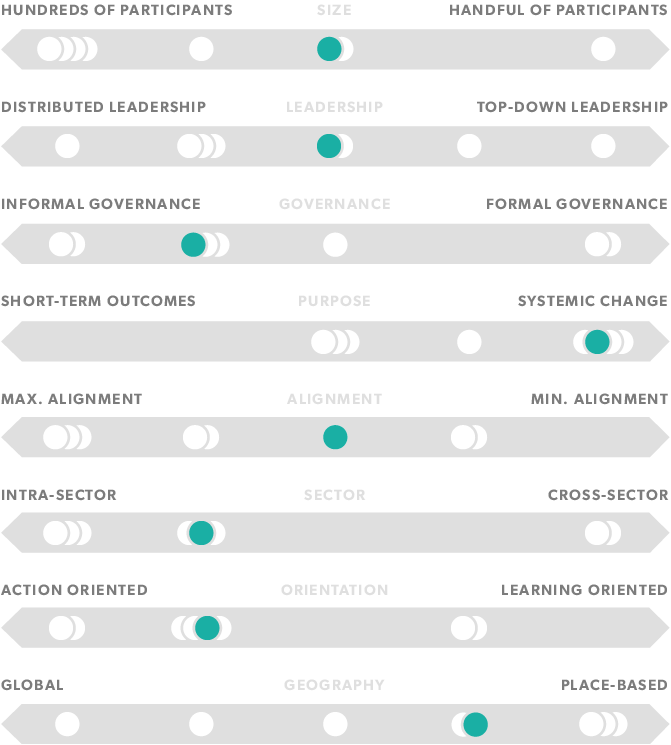

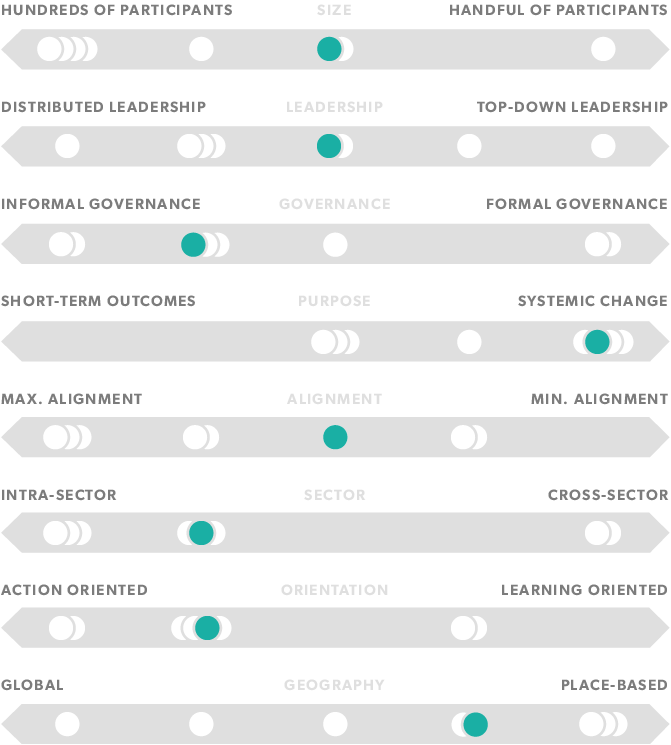

BY COMPARISON: THE NETWORK’S DESIGN

In the section What network design would be most useful? we introduce a simple framework for comparing the ‘design’ of a network — eight basic variables that define its shape and size. See below for our estimation of Reimagine Learning’s design (in teal) versus that of the other networks we profile (in white):

Sources: Monitor Institute interviews in fall 2014 with Shruti Sehra at New Profit, Tracy Sawicki at The Peter and Elizabeth C. Tower Foundation, Shelly London and Ashley Sandvi at the Poses Family Foundation, and Stacy Parker-Fisher at the Oak Foundation; personal knowledge of Monitor Institute network facilitators Anna Muoio and Dana O’Donovan; and, 3 Steps to Collaboration That Tackle Society’s Toughest Challenges (March 11th 2013).