SPOTTING A DESIRE FOR CONNECTION

A key skill in engaging with networks is the practice of tracking shifts in your field and the ability to spot the early signals of an opportunity for forming new connections. The seeds of the Pioneers in Justice (PIJ) were sown by one funder who was alert in exactly that way and recognized an important shift in the landscape of social justice work in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Bay Area is home to many leading social justice nonprofits that have been around for decades, and in the late 2000s five of these legacy organizations were undergoing a significant transition. While their traditional ways of operating were still effective, the digital age had ushered in new tools and approaches that many had not yet fully embraced—and weren’t sure how to embrace. Recognizing that they needed to update their methods, the boards of these nonprofits had hired new executive directors—all of them “Generation Xers”—whom they hoped could lead their organizations into the twenty-first century.

These five leaders came from a range of personal and professional backgrounds, with different ethnicities and leadership styles. But they also had a lot in common: all of them wanted to help their nonprofits adapt to a rapidly changing world; they were devoted to making a difference; and they all had a similar mandate. They were charged with evaluating the state of their field, formulating a vision for their organization’s future, and then executing on it—in short, helping to transform the nonprofits they had inherited.

Tim Silard, president of the San Francisco-based Rosenberg Foundation and a prominent figure in Bay Area social justice, had noticed the wave of new hiring and quickly recognized it as a critical inflection point for local advocacy groups—a “changing of the guard.” So he invited these five new leaders to lunch to get to know them better.

“The idea was not to have any formal agenda, but to create a sounding board, a place where they could kick ideas around with their peers,” Silard says. At that first lunch, the group talked about relationship building and staff and board issues. At the end, Silard asked if they wanted to continue meeting: he offered to be present, or just foot the bill for lunch. Either way, he sensed that it was important for these young leaders facing daunting challenges to have the time and space to talk together and learn from one another.

BROADENING THE LENS TO AIM FOR SYSTEMIC IMPACT

Many skilled program officers have developed Silard’s matchmaker instincts, but often their foundation’s structure and goals aren’t oriented towards supporting the next steps required to take a nascent network forward. But in this case, at the same time Silard was organizing the lunches, a shift in thinking was underway at the Levi Strauss Foundation (LSF). For decades, the foundation had operated like many traditional grantmakers, with most of its impact coming from grants given to nonprofits. But many of the foundation’s leaders were looking at the nature of today’s social challenges and wanted to test new approaches that might amplify LSF’s impact and reach. “We didn’t want to just give money,” says Bob Haas, president of LSF since 1990 and the great-great-grandnephew of Levi Strauss. “We wanted to do something that would move the dial.”

The foundation decided to search for new ways to drive systemic change, starting with the grantmaking in its own hometown. The goal it set was to find a way to use all the tools at its disposal to help local social justice organizations advance and accelerate their work. It described its new approach in a whitepaper in the following terms: “Social justice philanthropy encourages a foundation to use all the leadership tools at its disposal—that is, acting as convener, organizer, relationship broker, constituency builder, listener, policy promoter, and knowledge disseminator. It creates a platform for a more honest exchange between foundations and practitioners and aligns with what many consider ‘high-touch’ and ‘strategic’ grantmaking.”

LSF saw this definition of ‘social justice philanthropy’ as being at the vanguard of philanthropy: a greater focus on root causes, systems-level change, community empowerment, boundary crossing, and the use of multiple tools and tactics. The foundation’s leaders hoped that this concept would not only guide their own success but also mark a path for other grantmakers. “Our founder was a pioneer, and we like to think of ourselves as pioneers at the foundation,” says Bob Haas. “We’re willing to step out and take risks on behalf of what we believe is the right thing to do.”

DISCOVERING THE NEED FOR A NETWORK

It can be quite challenging for a foundation to find an intervention that lives up to such ambitious aspirations, since the opportunities to achieve systems-level change aren’t always available (or at least visible) when program officers go out on the hunt. But LSF lucked into a perfect opportunity with the group that Silard had begun to foster. It was in the fall of 2009 that Merle Lawrence, senior manager at LSF, and CJ Callen, a consultant to LSF, were busy interviewing “key informants” in the social justice sector, gathering information about how the foundation might retool its strategy to effect greater change in the field. Among the leaders they interviewed were former LSF grantee Lateefah Simon and the new executive director of the ACLU of Northern California, Abdi Soltani, who told them of the lunches that Silard had recently started.

Lawrence and Callen interviewed the pair in September, floating the nascent idea of an LSF-funded program that would convene a network of young social justice leaders and help build their capabilities to use social media and collaborative action to advance their missions and movements. Soltani’s reaction? “I already have a network, a ‘crew’ of people under 40: Lateefah, Titi, Vin, Arcelia, and me,” he told them. Astutely, Lawrence sensed an opportunity and asked what this cohort needed to amplify its work. Over the course of that initial conversation, the main themes of a new program emerged—one that would both match the needs of these new executive directors and engage LSF in cutting-edge work.

The young leaders’ wish list resembled that of many legacy nonprofits across the country. They requested “time and space” to figure out how they wanted to lead and how they might collaborate with one another. They also wanted to find ways to empower their constituents to speak for themselves while broadening and diversifying their aging membership base. Lastly, these leaders wanted to address what Simon called the “crisis of translating social justice work” into social media in order to influence public perception.

In November 2009, after several interim committee meetings and lots of iteration on the idea, Lawrence and LSF executive director Daniel Lee presented their initial vision to the full LSF board. They recommended that the foundation support a group of young leaders looking to shape the next wave of social justice work for bedrock civil rights organizations. “We wanted to help equip them and their organizations with the technical skills to use social media to full effect,” says Jennifer Haas, LSF trustee. “We also wanted to help them harness the power of collaboration and their people-to-people networks as a way to maximize their impact.”

While no one was clear yet exactly what the program would look like, which specific individuals should be in it, or how it might evolve as the leaders and LSF learned along the way, the LSF board recognized the plan as a significant opportunity for the foundation to shift into deeper grantee engagement. And funding a broad platform that focused on leadership development and coalition building was just the sort of high-risk, high-reward strategy that the LSF board had in mind. (Crucially, the LSF board wasn’t concerned about building on work that Silard had started. The board members could see that there was still ample opportunity for them to take it further.)

Between the spring and fall of 2010, LSF refined its definition of who should be in the program, deciding to focus exclusively on San Francisco-based organizations and ultimately on the leaders who were already part of the nascent cohort that Tim Silard had convened. LSF senior manager Merle Lawrence, who retired in 2013, attended one of Silard’s lunches and laid out the program to four of the five young executive directors to gauge their reaction and gather their input. The program aimed to spark change on several different levels, by strengthening their leadership, helping their organizations transform, and giving them the time and space—and the funding—to experiment with new ways of spreading their reach and building social movements.

Recognizing that this kind of change would take time and commitment, the board initially approved the initiative to run for three years and agreed that the LSF staff should be highly involved and hands-on. In fact, LSF explicitly did not want to run the program like a traditional grantmaker. Instead, it wanted the relationship between itself and the program’s grantees to be a partnership. LSF would not dictate the terms and conditions, but rather commit to working with the cohort to structure the emergent initiative as it evolved.

In November 2010, the LSF board met the five Pioneers in Justice for the first time, learning more about their backgrounds, their stories, and their passion for driving change in their organizations and in the world. Based on what they heard, the board unanimously approved to extend the initiative to five years in order to give the cohort more time to bring about the kinds of transformation they wanted.

PROVIDING A CONTAINER AND PLAYING THE “RIGHT” FUNDER ROLE

What allowed LSF to take full advantage of this opportunity was the way it chose to engage, carving out a very different role for itself with the Pioneers than it typically played with grantees. It was clear to LSF from the beginning that this was not the kind of grantmaking that would have a tangible list of deliverables with fixed timelines. Nor would PIJ easily lend itself to traditional impact assessment. Rather, it would be emergent and filled with experimentation.

From the start, LSF envisioned the program as one that would be co-created with the Pioneers, starting from a place of empathy and inquiry. “This work is animated by really basic questions: What do you all need? What would you like to try?” explains Linda Wood, senior director at the Evelyn & Walter Haas, Jr. Fund and an advisor to the LSF staff as they developed the PIJ network. She also notes how distinct this approach is for most funders: “It takes a really humble funder to help leaders and their organizations learn what they need to learn through experiments and through one another.”

Whenever the Pioneers and LSF describe the unpredictable journey of this work, they regularly use the words “messy” and “risky.” In August 2010, when PIJ officially kicked off, each of the five organizations and leaders were at different points in their journey toward social justice 2.0. They knew that some would get further than others, faster, and failures could and would occur. But throughout the process, the Pioneers have been honest about their challenges and frustrations and embraced their setbacks, allowing all of them to learn valuable lessons as a result.

Despite the innovative and experimental nature of PIJ as a startup network, LSF knew it had to create some sort of handrails or “container” for the work to happen. They deliberately designed the program around several building blocks, without overly prescribing how each one would evolve:

- Bimonthly, half-day forums dedicated to peer-to-peer learning, case studies, and training. These were opportunities for the Pioneers to share their experiences, learn together, and support one another. LSF was both the organizer and a participant in these sessions, often bringing in leading experts on networks, social media, and more to help the Pioneers move from theory to action.

- Capacity building grants to help the Pioneers create the requisite technology infrastructure, strategies, and communications skills needed to integrate social media more deeply into their organizations. LSF’s technical partner, ZeroDivide, provided social media training for both the Pioneers and their staff, helping them build a sustainable, integrated social media practice within their organizations.

- Collaboration grants to support project-based work and “experimental” collaborations that reached across sector, field, issue, and constituency, using networks of both trusted and “unlikely” allies to drive change.

In the first two and a half years of the five-year program, LSF invested close to $2.9 million in 44 grants, including $1.72 million for capacity building and $580,000 for supporting three collaborative projects. LSF is a modestly resourced foundation, with an annual budget ranging from $7 million to $8 million; support for PIJ represented 18 percent of its giving and 80 percent of Lawrence’s time, in addition to the contributions of two other staffers.

The program was a significant investment for the foundation, but its staff and leadership understood what was required to match the complexity and ambitions of the program. As Lee reflects, “The investment we’ve made in this program has been substantial—both in terms of financial support and the leveraging of our other resources, such as space, staff time, and partnerships. But our learning has been equally significant. We have learned a tremendous amount about how to invest in and support leadership networks as a tool for transformative social change. This kind of work is messy. It involves embracing both complexity and emergence, and it doesn’t lend itself to linear logic models, anticipated outcomes, or overly narrow metrics. But when it works—as we believe this program is beginning to demonstrate—it holds enormous potential for increasing our social impact on multiple levels of the larger systems we seek to transform.”

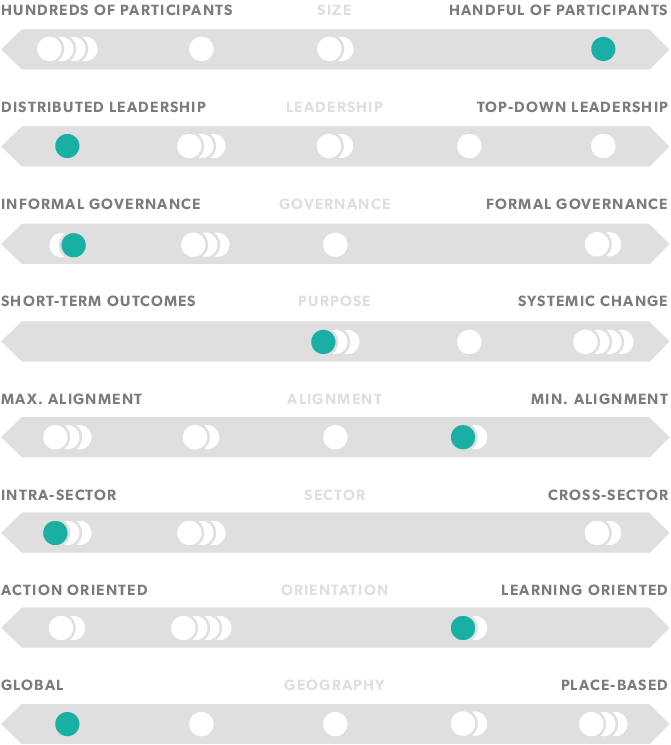

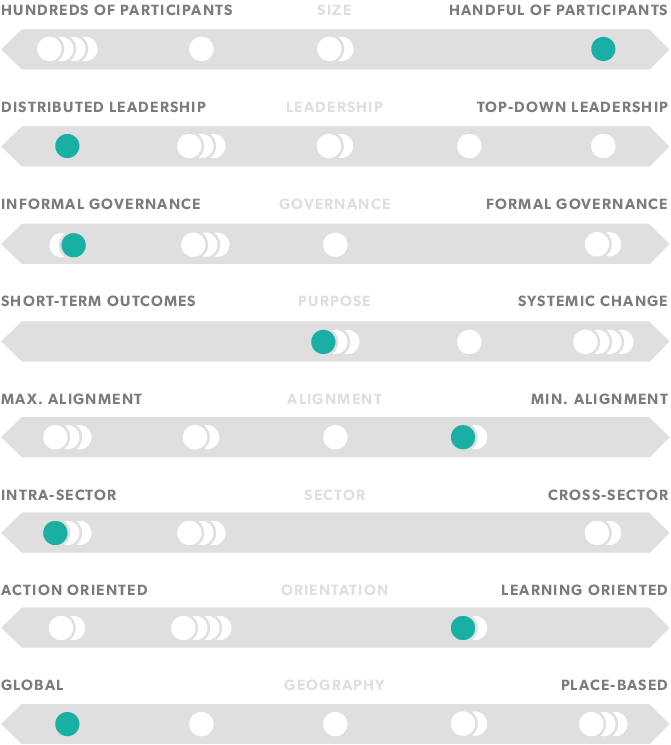

BY COMPARISON: THE NETWORK’S DESIGN

In the section What network design would be most useful? we introduce a simple framework for comparing the ‘design’ of a network — eight basic variables that define its shape and size. See below for our estimation of the Pioneers in Justice network’s design (in teal) versus that of the other networks we profile (in white):

This story sketch is constructed from excerpts of Pioneers in Justice: Building Networks and Movements for Social Change by Heather McLeod Grant, the comprehensive case study published by Levi Strauss Foundation in 2014.